This article appeared earlier today in the Observer section of the Guardian.

From its founding in 1932 until 1998, Lego had never posted a loss. By 2003 it was in big trouble. Sales were down 30% year-on-year and it was $800m in debt. An internal report revealed it hadn’t added anything of value to its portfolio for a decade.

Consultants hurried to Lego’s Danish HQ. They advised diversification. The brick had been around since the 1950s, they said, it was obsolete. Lego should look to Mattel, home to Fisher-Price, Barbie, Hot Wheels and Matchbox toys, a company whose portfolio was broad and varied. Lego took their advice: in doing so it almost went bust. It introduced jewellery for girls. There were Lego clothes. It opened theme parks that cost £125m to build and lost £25m in their first year. It built its own video games company from scratch, the largest installation of Silicon Graphics supercomputers in northern Europe, despite having no experience in the field. Lego’s toys still sold, particularly tie-ins, like their Star Wars and Harry Potter-themed kits. But only if there was a movie out that year. Otherwise they sat on shelves.

“We are on a burning platform,” Lego’s CEO Jørgen Vig Knudstorp told colleagues. “We’re running out of cash… [and] likely won’t survive”

In 2015, the still privately owned, family controlled Lego Group overtook Ferrari to become the world’s most powerful brand. It announced profits of £660m, making it the number one toy company in Europe and Asia, and number three in North America, where sales topped $1bn for the first time. From 2008 to 2010 its profits quadrupled, outstripping Apple’s. Indeed, it has been called the Apple of toys: a profit-generating, design-driven miracle built around premium, intuitive, covetable hardware that fans can’t get enough of. Last year Lego sold 75bn bricks. Lego people – “Minifigures” – the 4cm-tall yellow characters with dotty eyes, permanent grins, hooks for hands and pegs for legs – outnumber humans. The British Toy Retailers Association voted Lego the toy of the century.

Brick by brick: inside the Lego offices in Billund, Denmark. Photograph: Redux/Eyevine

When The Lego Movie came out in 2014 the film snob website Rotten Tomatoes awarded it a 96% approval rating: only Oscar nominees 12 Years a Slave and Gravity matched it. This year’s follow-up, The Lego Batman Movie, outperformed the last “proper” Batman movie, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, to such a degree that DC Comics now faces a genuine problem: audiences overwhelmingly prefer the Dark Knight in his pompous and plastic version voiced by Will Arnett, rather than Ben Affleck’s portrayal.

Lego’s revival has been called the greatest turnaround in corporate history. A book devoted to the subject, David Robertson’s Brick by Brick: How Lego Rewrote the Rules of Innovation, has become a set business text. Sony, Adidas and Boeing are said to refer to it. Google now uses Lego bricks to help its employees innovate.

Lego’s saviour is the aforementioned Vig Knudstorp – a father of four, perhaps not uncoincidentally – who arrived from management consultants McKinsey & Company in 2001 and was promoted to boss within three years, aged 36. “In some ways, I think he’s a better model for innovation than Steve Jobs,” Robertson has said.

A model of the new Lego House in red, yellow, green and blue

Last month I flew to Billund, a small town in the Jutland peninsula where Lego was founded. The landscape was flat and grey, but as I drove from the airport a large primary coloured arm or head would occasionally appear though the pine trees: the Lego Group owns several buildings here and has decorated the landscape accordingly. I was immediately in a good mood.

Boys are more about good versus evil, but girls really see them-selves through the Mini-doll

“Billund was built to function, not to please,” explained Roar Trangbaek, Lego’s cheerful, bearded publicist. “There’s not a lot of fun here.” He meant there wasn’t a lot to do there – it’s hard to imagine the nightlife is up to much – but given that 120m Lego bricks are manufactured here every day, fun was very much the point of the place. As if to prove it, Trangbaek handed me his business card. It was a Minifigure of himself.

The following morning the Lego Group was due to announce its latest annual results. Today was an opportunity to meet some of its key employees, tour the factory and be among the first to step inside Lego House – a 130,000sq ft marvel that will open in September, and is expected to draw 250,000 visitors a year. It has been designed by Bjarke Ingels, the hottest name in architecture right now, whose commissions include Google’s HQ, the new World Trade Center and last year’s Serpentine Pavilion. Ingels certainly seems to have enjoyed himself: Lego House resembles 21 giant Lego bricks stacked into a 30m tower. Visitors can climb up to the rooftop garden and down the other side, pausing to take in attractions, restaurants, play zones and a gallery dedicated to fan-made Lego extravaganzas. Life-sized Lego sculptures had been placed around the interior – a cop, a firefighter – while real-life construction workers in hi-vis tabards beavered away around them, a surreal sight.

Toy story: CEO Jørgen Vig Knudstorp’s Minifigure. Photograph: Camera Press

Lego had compensated for the disruption to the town’s shops by allowing them to exclusively sell Lego kits of the Lego House, the only place in the world they’ll be available. (For Lego’s numerous cult fans, this is a massive deal.)

Vig Knudstorp rescued Lego by methodically rebuilding it, brick by brick. He dumped things it had no expertise in – the Legoland parks are now owned by the British company Merlin Entertainments, for example. He slashed the inventory, halving the number of individual pieces Lego produces from 13,000 to 6,500. (Brick colours had somehow expanded from the original bright yellow, red and blue, sourced from Piet Mondrian, to more than 50.) He also encouraged interaction with Lego’s fans, something previously considered verboten. Far from killing off Lego, the internet has played a vital role in allowing fans to share their creations and promote events like Brickworld, adult Lego fan conventions. A year before James Surowiecki’s landmark book The Wisdom of Crowds was published, Lego launched its own crowdsourcing competition: originators of winning ideas get 1% of their product’s net sales, designs that so far include the Back to the Future DeLorean time machine, the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine and a set of female Nasa scientists.

“Lego has this incredible ability to engage with people and that has single-handedly enabled it to weather very, very difficult seas,” says Simon Cotterrell, from brand analytics firm Interbrand. “What’s made them successful over the past 10 years is their ability to create new entities, movies, TV shows, by partnering with brilliant people. They’ve said: ‘We might not make as much money if we outsource it, but the product will be better.’ That mentality is very Danish. It comes from saying: ‘We’re engineers. We know what we’re good at. Let’s stick to our knitting.’ That’s a very brave thing to do and it’s where a lot of companies go wrong. They don’t understand that sometimes it’s better to let go than to hang on.”

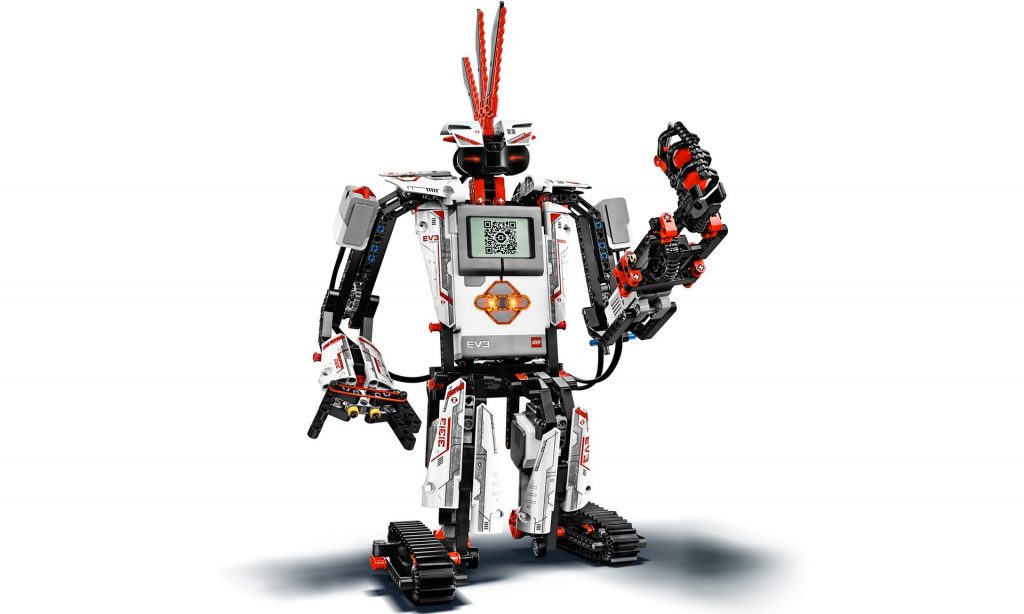

It also started making hit toys again. As well as putting a focus back on classic Lego lines like City and Space, it has launched the ninja-themed Ninjago line, Mindstorms, kits that allow you to build programmable Lego robots, aimed at teens. And for grown-up kids, Lego Architecture, replicas of the Guggenheim, Burj Khalifa and Robie House, that last one not for the feint-hearted or time-poor – it contains 2,276 bricks. Most impressively for a company with a customer base that in 2011 was 90% boys, it finally cracked the girls’ market. Lego Friends features a reconfigured “Mini-doll” and centres on five characters in the fictional Heartlake City. None of this has happened by chance. Lego is said to conduct the largest ethnographic study of children in the world.

Go figure: Batman, from the Lego film. Photograph: Warner Bros. Pictures/AP

“We call it ‘camping with consumers’,” says Anne Flemmert Jensen, senior director of its Global Insights group. “My team spends all our time travelling around the world, talking to kids and their families and participating in their daily lives.” This includes watching how kids play on their own and with friends, how siblings interact and why some toys remain perennial favourites while others are relegated to the toy box. Children are fickle – as the makers of forgotten “must-have” Christmas toys, like Pogs and Furby, will concede.

Ninjago was crowdsourced: its first iteration featured skeletons as enemies because tests proved they were the most popular baddies among six-year-old boys, globally. “Ninjas crystallised themselves because we were, like: ‘What’s the greatest hero entry point?’” says Cerim Manovi, senior design manager and creative lead on the line. “We showed them superheroes, everything – but ninjas just grabbed kids right there.”

Lego Friends took four years of research (plus a $40m global marketing push) to get right.

“One of the main things was they couldn’t really relate to the Minifigure,” says Mauricio Affonso, Friends’ model designer. “It’s too blocky. Boys tend to be a lot more about good versus evil, whereas girls really see themselves through the Mini-doll. They wanted a greater level of detail, proportions and realism.”

Lego Friends sets (bakery, amusement park, riding camp, etc) tend to feature something else missing from boys’ sets: a loo. The boys don’t care, the girls’ pragmatism demanded it.

Girl guides: designing the Lego Friends dolls. Photograph: Niels Aage Skovbo

Roar Trangbaek shows me the original Lego house, where the company’s founder Ole Kirk Christiansen lived. It’s now a private museum that tells the Lego chronology through artefacts, packaging and toys. More than one adult visitor has been known to burst into tears when confronted by a key line from their childhood: in my case the Space Lego of the mid-1970s. (Lego gets inundated with requests for re-releases, but they won’t do it. Their focus is the kids of now and tomorrow, not yesterday.) Christiansen was an expert carpenter when the Great Depression hit. He figured the one thing people would always find money for was toys for their children. His company motto is carved into a plaque here – “det bedste er ikke for godt” (Only the best is good enough) – something borne out when Christiansen’s son Godtfred returned home one day to proudly inform dad he’d saved them some cash by only applying two of the usual three coats of varnish to a wooden duck. He got a tongue- lashing for his trouble.

“It is a good story, but it’s also a true story,” says Trangbaek.

Lego Life is a social network for kids too young for Instagram to share their creations, gaining ‘likes’

In 1946, against everyone’s advice, the family invested in a newfangled plastic-injection moulding machine. Later they adapted Croydon-based inventor Hilary Fisher Page’s self-locking bricks (billed his “sensible toy”) – plastic cubes with two rows of four studs to enable stacking. The final part of Lego’s success clicked into place in 1958 when it created its “system”. Where previously they’d made toys of all shapes and sizes now every brick fitted with every other: everything was backwards compatible. “We’ve got the bricks, you’ve got the ideas,” advised a 1992 Lego catalogue. A mathematician recently deduced that just six eight-stud bricks of the same colour could be combined 915,103,765 ways.

During the factory tour we saw some of those bricks being created. Here, 768 moulding machines work 24/7, 361 days of the year. There was a constant hiss: the sound of raw granulate being fed into the vast machines. Then something akin to Wonka magic, brightly coloured pieces of joy materialising at the other end. Lego’s quality control and precision is rigorous. As any parent who’s trodden on a piece knows, Lego is hard. The bricks have to be strong enough to hold together, but not so strong they can’t easily be pulled apart by a child. They call it “clutch power”. It is a huge industrial process, with similar plants in Hungary, China and Mexico. “Our idea is to have factories located close to key markets,” Trangbaek explained. Most companies make product where it’s cheapest then ship it. Not Lego. “It’s much more costly for us to lose a sale,” he said. “If you go to a toy store and you don’t find the product there on the shelf, you will be disappointed. But you will also not leave the shop without another toy.”

Teen dream: the Mindstorm robot.

Lego is increasingly concentrating on bridging the physical and the virtual. This year it rolled out Lego Life, a social network for kids too young for Instagram to share their creations, gaining “likes” from peers and Lego characters alike. “Lego Batman can comment in character. ‘That’s awesome – would have been better in black and yellow,’” says Dieter Carstensen, head of digital child safety and the Lego Life team.“That kind of stuff.” There’s also Nexo Knights, a video game where powers are unlocked by scanning Lego pieces. They’re researching VR and AR. “Some of the things we’re looking at are very near to being feasible now,” says William Thorogood, an irrepressibly bouncy Brit, and the senior innovation director with Lego’s creative play lab. “Other things are very exciting, but probably not feasible for 10 years, depending on how mature the tech becomes.” Later this year we can look forward to The Lego Ninjago Movie, whose tone looks every bit as irreverently daft as its predecessors.

The next morning in Billund, Lego announced the highest revenues in its 85-year-history. Since December the company has been run by another Brit, Bali Padda, the first non-Dane in charge, after Vig Knudstorp moved into a new role to expand the brand globally. Asia, with its booming middle class, is a focus.

Block party: Lego’s production plant in Billund. It makes 120m bricks a day. Photograph: Redux/Eyevine

“The reality is that the last few years the growth has been supernatural,” Julia Goldin, Lego’s chief marketing officer, tells me. “When you look at the proportion of revenue that’s coming out of the mature markets it becomes more and more challenging with the level of penetration. But we look at every year starting at zero because you have to recruit every child again and make the brand exciting for them. That becomes a good challenge, of course.”

Earlier I had met Bo Stjerne Thomsen, the director of research and learning with the Lego Foundation, an independent body that owns 25% of the Lego Group and studies early childhood development through play. (It has partnered with Unicef in South Africa, and funded the world’s first professor of play, at Cambridge University)

Thomsen produced two plastic bags containing a few red and yellow bricks, part of a basic kit they use to engage learning.

“Quickly build a duck,” he instructed me. “Everybody can usually do it in 40 seconds.”

We set to work. Thomsen’s duck had two outstretched wings. Mine had a red bill, a red slab for feet and a yellow block for a tail.

“Oh, that’s fun!” he said. “I like that.”

There was no wrong or right duck, of course. That was the point. “It’s about the process of making and investigating and learning,” Thomsen said.

“How fast do you think anyone can do a duck?” Thomsen asked.

I’m not sure, I said. Ten seconds?

“Ten seconds? OK, let me count.”

Then he slammed another set of pieces straight down on to the table.

“That’s my duck!” he beamed. “I just sliced it up so it’s ready for the oven. Ha ha!”

Lego is a serious business. It just happens to be in the business of fun.

Become a LEGO Serious Play facilitator - check one of the upcoming training events!

Become a LEGO Serious Play facilitator - check one of the upcoming training events!