Edwin de Vos and Dieter Reuther suggested the following interesting article from the Boston Globe, written by Leon Neyfakh.

The adult human is a serious animal: a worker, a thinker, a problem solver. He or she strives for focus and efficiency, resisting frivolity in the name of being a grown-up and staying on task.

OK, so maybe that’s not always true. If it were, there probably wouldn’t be Ping-Pong tables popping up in America’s trendiest office buildings or karaoke nights in downtown Boston. And there probably wouldn’t be so many funny dog videos on Facebook or such a premium placed in social situations on making other people laugh.

The fact is, even the most responsible adults occasionally indulge in what can only be described as playfulness: pursuing delight in all its forms, engaging in friendly, low-stakes competition, and investing precious resources in amusing themselves and others. While it’s easy enough to say from personal experience that we do this stuff because it’s fun, scientists who specialize in the psychology of play have only recently started getting a grip on what it is that makes otherwise self-possessed, mature adults inclined toward fooling around and being silly—and what long-term benefits they get out of it.

“Adults are playful—that’s a fact,” said René Proyer, a psychologist at the University of Zurich who has written more than a dozen papers on adult playfulness over the past three years. “[But] psychologists haven’t thought much about this, probably because it wasn’t deemed worthy enough.”

What Proyer and the other researchers who have recently moved to fill that gap are discovering is that playfulness, as a personality trait, is not only complex but consequential. People who exhibit high levels of playfulness—those who are predisposed to being spontaneous, outgoing, creative, fun-loving, and lighthearted—appear to be better at coping with stress, more likely to report leading active lifestyles, and more likely to succeed academically. According to a group of researchers at Pennsylvania State University, playfulness makes both men and women more attractive to the opposite sex.

But wait: Before you run to the store to buy a yo-yo and a pair of roller skates in hopes of nailing your next exam or upping your romantic game, you should know that the whole endeavor of researching playfulness in adults involves a conundrum. As British researchers Patrick Bateson and Paul Martin argue in their 2013 book, “Play, Playfulness, Creativity and Innovation,” it’s crucial to distinguish between engaging in behavior that is technically play—battling it out in an intense game of tennis, for instance, or wasting time on an addictive iPhone game—and doing it in a way that is actually playful, which for Bateson and Martin means “cheerful, frisky, frolicsome, good-natured, joyous, merry, rollicking, spirited, sprightly [and/or] vivacious.” An important challenge facing researchers in this field is figuring out how to isolate and define playfulness as an internal state of mind rather than a mere description of how someone is acting.

“Playfulness is something even laypeople can recognize when they see it,” said Xiangyou Sharon Shen, a research consultant with a PhD in leisure studies from Penn State who has developed a psychological instrument to determine a person’s predisposition toward playfulness. “But playfulness research is still in its infancy, in that there’s a lot of confusion and disagreement surrounding what playfulness even is, and how to measure it.”

It might seem ironic, even counterproductive, to try to nail down and analyze something as ineffable as “playfulness” as though it were a dead insect on a pin. But as researchers learn more about how it fits into the structure of human personality, it raises the hope that we can not only define playfulness scientifically, but actually teach ourselves to incorporate it into our lives, long after we’ve put our toys away.

The subject of play has attracted the interest of some of history’s great minds, including Charles Darwin, who was curious about the mechanics of tickling, and Sigmund Freud, who wrote about the role of play in emotional development. With few exceptions, however, psychologists interested in play have focused on children rather than adults. Over the years, a wealth of research has suggested that child’s play is an important part of growing up—that, among other things, it helps kids “practice” for the real world by prompting them to solve problems and deal with emotions they might encounter later in life.

Playfulness in adults did not become a significant area of research until recently—perhaps because play tends to become less central as people get older. “I think it just didn’t seem as respectable as other things, which is too bad,” said Scott Eberle, the editor of the American Journal of Play. “The grave and the serious seem more important than the way we find levity in our lives.”

One of the first researchers to break with this tradition was Mary Ann Glynn, now a professor at Boston College, who, along with her coauthor Jane Webster, published a paper in the early 1990s that described adult playfulness as “a predisposition to define and engage in activities in a nonserious or fanciful manner to increase enjoyment.” Based on a series of lab experiments and surveys, Glynn and Webster concluded that playfulness in adults was linked to “innovative attitudes” and “intrinsic motivational orientation,” meaning playful people were more likely to do things without regard for their practical purpose. The researchers also found that when study participants were asked to compose sentences using a specific set of words and told to treat the task as work, they exhibited less creativity and figurative thinking than people who were primed to approach the exact same task as play.

Glynn didn’t end up staying in the adult playfulness lane for long; she now studies innovation in large organizations. But in the past decade or so, a crop of researchers, including Proyer and Shen, have begun chipping away at the subject again with new rigor. There are now four separate psychological “scales” designed to measure people’s inclination toward playful thinking and behavior. Multiple conferences have been held to discuss the value of play in the past several years. There is even a 10-hour documentary TV series being developed called “Now Playing,” about “the vital importance of play to our happiness, well-being, and the future of life.”

According to Proyer, part of the reason for the recent boomlet in adult-playfulness research is the concurrent rise of positive psychology and its premise that it’s just as useful to understand happiness and well-being as sadness and dysfunction. The research on adult playfulness is still in its early stages, Proyer said. “Honestly speaking, psychology is way behind reality here,” he said. “Because if you look at the entertainment industry—if you look at some of the computer games that they sell…they are directed at adults. You have amusement parks where you have some of these rides that children aren’t even allowed to go on.”

One of the most interesting findings Proyer has generated so far is that playful people perform better academically—a discovery he made after conducting a study on his own students over the course of a semester. “The more playful the students were, the better the grades were,” he said. (He pointed out that the course in question was extremely challenging and technical, not one where being particularly playful would confer an obvious advantage the way it would in, say, clown college.)

Another intriguing finding, reported by University of Illinois associate professor and playfulness expert Lynn A. Barnett, is that playful people are less likely to encounter stress in their lives, and that when they do, they’re better at coping with it. “People who are playful don’t run away from stress, they deal with it—they don’t do avoidance,” Barnett said.

In a separate study, Barnett found that people who scored high on her playfulness test were much better at entertaining themselves when forced to sit in an empty, boring room than people who didn’t. “The low-playfulness people hated it. They couldn’t wait to get out of there,” said Barnett. The high-playfulness test subjects, on the other hand, actively enjoyed being in the boring room, even though surveillance camera footage showed that they didn’t do anything but sit still while they were in there. “They were just in their heads—they entertained themselves.,” she said.

Another study, coauthored by Penn State professor Garry Chick, found that when asked about qualities they looked for in potential romantic partners, participants said they preferred playful people. Chick theorizes that this has evolutionary roots: Playfulness makes men seem less threatening to women, and women seem younger to men—and thus more fertile. A separate study conducted at Penn State, this one focused on the elderly, showed that playfulness in later life is associated with better cognitive and emotional functioning.

In the future, said Proyer, we can look forward to the results of studies, already underway, about the role playfulness plays in happy romantic relationships, and the possibility of a perfect ratio of playful to not-playful people when it comes to groups working together in a professional capacity.

***

It’s clear that playful people have a better time. But are you stuck with the level of playfulness that comes naturally to you, or is it something you can knowingly cultivate? “It’s the 64 million dollar question,” said Barnett, noting that the one relevant study she’s aware of, in which researchers tried to train children to become better at pretend-play, ended in failure.

Most researchers in the field seem optimistic, though. Pat Bateson, for one, says playfulness should be seen not as a fixed trait but rather as a mood that some people are more likely to express than others. That being the case, he wrote in an e-mail, he hopes that “non-playful people can be encouraged to become more playful.”

Even those researchers who do think of playfulness as a personality trait—a way of being in the world that persists over time and across situations—suspect it’s a malleable one, which people can develop in themselves if they want to. To test this hypothesis, Proyer is working on what he calls a series of “intervention” programs designed to help people become more playful.

There is an obvious irony hanging over the entire field, and one its researchers are aware of. The minute you identify “play” as something that matters because it’s useful, it stops being play. As Anthony Pellegrini, an education psychologist and author of the 2009 book “The Role of Play in Human Development,” put it, “What play is—and this is a crucial distinction, especially when you get to adults—is an a orientation where the means are more important than the ends, where you’re much more concerned with the process than the result.” For example, a person who goes swimming during lunch every day to enjoy himself, like Pellegrini does, may be doing something playful. A swimmer in the next lane over who’s there to lose weight or train for an important race may not be.

That might make it seem self-defeating to try to become more playful: If people engage in such behavior for a pragmatic reason, it might not really be play at all. According to Barnett, this is what’s tricky about actively making use of the findings that she and others in her field have generated: “If you’re self-monitoring, that’s going to get in the way of being playful,” she said. “A lot of playfulness is spontaneity, unpredictability, just being adventurous. As soon as you employ your more rational cognitive faculties, I think you’re interfering with it.”

That doesn’t mean that adults—even the most goal-oriented among us—can’t ever be truly playful in the way we used to be as children. It just means we need to allow ourselves to indulge in the pleasures of pointless or sheerly enjoyable activity, whether that means board games, dancing, pulling pranks, or making other people laugh. Growing up, in other words, doesn’t have to mean cutting fun and lightheartedness out of our lives. On the contrary, it may mean realizing that engaging in such childishness is an excellent use of our time.

Leon Neyfakh is the staff writer for Ideas. E-mail leon.neyfakh@globe.com.

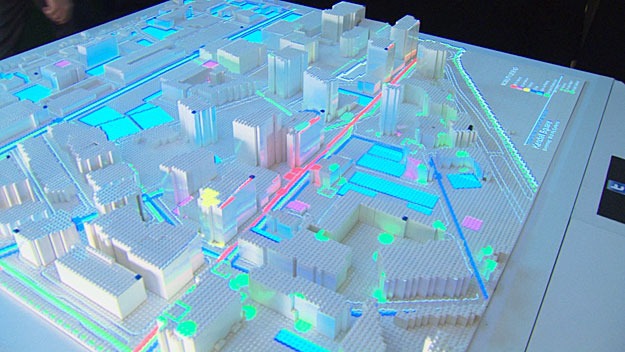

Become a LEGO Serious Play facilitator - check one of the upcoming training events!

Become a LEGO Serious Play facilitator - check one of the upcoming training events!